The inspiring story of legendary Saluki running back Andre Herrera

- Tom Weber

- Aug 11, 2025

- 11 min read

Updated: Aug 15, 2025

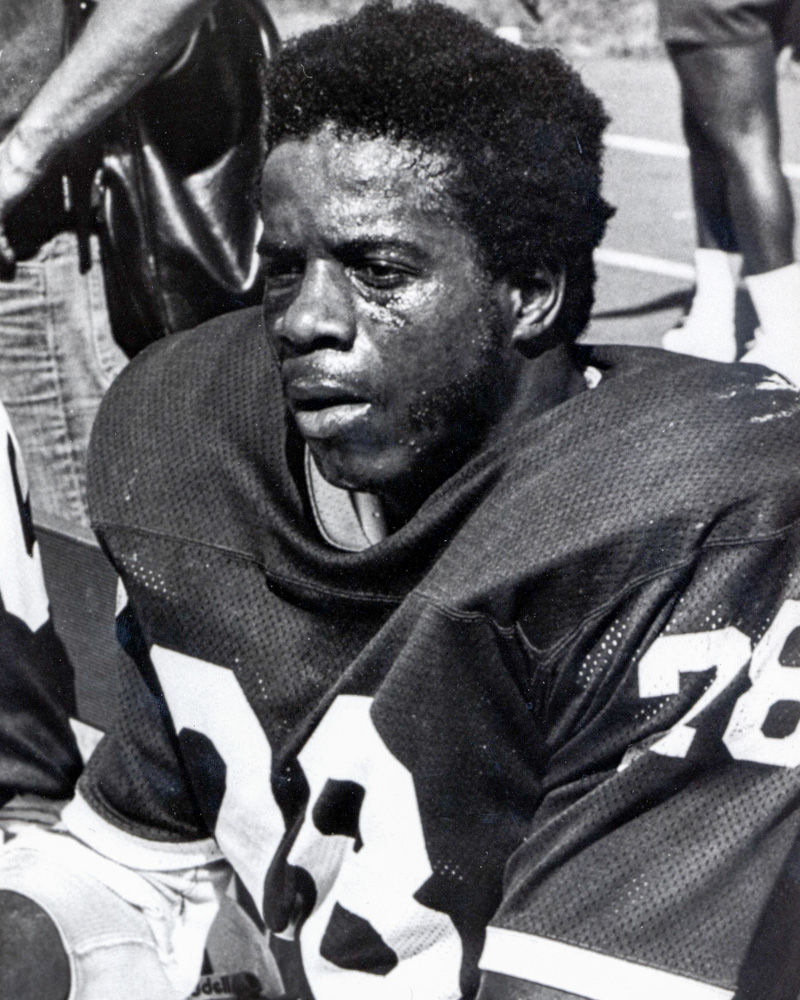

CARBONDALE, Ill. — One of the greatest running backs in Southern Illinois history is Andre Herrera. His record-setting season in 1976 was so remarkable, that he was one of only four players to receive votes for the United Press International College Football Player of the Year award (Tony Dorsett, Vince Ferragamo and Ricky Bell were the others). In fact, he finished second in the nation in rushing yards behind Dorsett that season.

From the projects of the Bronx, to Carbondale, to the National Football League, to a highly successful career in sales — here is his incredible and inspirational story.

StrongDawgs: Tell me about your experience growing up in New York City.

AH: Growing up in New York City, in the projects of New York City, certainly given, given my druthers, I would not have wanted to be born in that kind of environment, but it taught me a lot. Card-boarding my shoes — I lived that life. I used to deliver milk in the projects at two o'clock in the morning until four or five and then go to junior high school. I was working in the summer.

I had an abusive father who didn't allow me to play any sports, said I would never amount to anything. I played baseball growing up, and they would tell my father, “you need to put him in Little League.” He refused to do any of that. So the physical-mental abuse was constant until he walked away from us when I was about 14. My mother was an angel. And she still is. She's not alive.

SD: How did you make it out of that situation?

AH: One of the first male figures and mentors in my life was a high school football coach in the Bronx named Mickey Bub. He was just a great mentor of young men and gave us a start in life and kept us on. I was playing sandlot football, which we’d get together on Sunday, remove the glass on the field, and he said, “why don't you go up to Westchester Community College and try out and get an education.” Mickey said to me, “you're wasting your time down here. You need to go do some other things.” So, of course, I agreed, and I told my mother I would not come back to the projects. I mean, I would come back to visit her, but I didn't want to come back to live. That environment had no future. It was during the epidemic of heroin.

I also had a big brother by the name of Michael Bostick, who was just a ton of inspiration.He's not related to me, but he's like my big older brother. And so off I went to Westchester.

SD: You were also recruited as a basketball player, but was football the sport you enjoyed the most?

AH: Yes, my love was really with football. I didn't have any training. I never went to football camps or anything like that. I would get a magazine at the newsstand and read about players doing phenomenal things, like Gale Sayers and Jim Brown. I just thought, okay, I'm going to do this. The one thing that was maybe the driving force was I was very competitive. I wasn't going to back down from anybody just because they had shiny shoes or they came with a reputation.

SD: How did your life change at Westchester?

AH: They had a very successful program, had won a national championship the year before. A lot of players that played in high school in the city and the Catholic high schools did very, very well there. Some who went there from the city dropped out academically. The environment was overwhelming.

Needless to say, they didn't know anything about me. I was stuck at tight end, down in the depth charts, and it was frustrating. But I was a late bloomer, so I started growing a couple of years prior to that, and I was very fast. Every time I caught the ball, it was abundant to the backfield coach that they should switch me to running back. I never played that before. The head coach refused, refused, refused.

So the first game, they were trying to highlight the quarterback, and the first game we played, he didn't do well and we lost. So everybody was upset because they never lost. The second game had the same strategy, and we lost again. So now the roof is about to collapse on a junior college in a program that was very, very successful. So the head coach said to the backfield coach, “alright, this time, we're going to try your way. We're going to run the football with number 28.” He was calling me Bullet, and we're going to run him. The end result was I had 144 yards in the first half, and that started me off.

SD: Your career numbers in two years at Westchester were amazing.

AH: I had just loaded them up week after week. We played a lot of four year schools, went against Iowa. I was All-American my first year.

When we went to the all-league luncheons and dinners, I like to tell this story with some humor. We sat down to eat. There were two forks, and one was smaller than the other. I thought they made a mistake, because I never sat down to eat where there were two forks. Of course, one is for a salad and one for a regular meal. I never ate out in a restaurant, I mean a McDonald's or anything until I went to college. We never had a car. So now I'm flying to a lot of places — University of Miami, Georgia, North Carolina State.

My second year, I was All-American again, and we were dominating a lot of teams, but I only carried the ball 11, 12 times a game, but I had eight yards per carry average. A lot of times they wouldn't play me because the other teams had indicated if they played me to run up the score, they wouldn't schedule them.

SD: How did you find your way to Carbondale from Westchester?

AH: So I was All-American again as a sophomore, and I was walking in the student center. This is before cell phones, so communication wasn't as prevalent as it is after the cell phone era. A guy asked me if I was Andre Herrera, I said, yes. He took out a piece of paper and said, “I’m going to give you a scholarship right here.” It was funny because it was the middle of the student center and people walking by going to class and he's asking me to go to school at SIU. Turns out my head coach was funneling people to Southern Illinois. They took two players prior to me.

When I came out to Southern, thank God. God’s guiding light and hand on me because I just fell in love with the people and thought it was a beautiful place.

SD: You arrived at Southern in 1974. How big of an adjustment was that for you?

AH: Picture someone that grew up in New York City and the projects coming to southern Illinois, which is vastly different, just everything about it, what kind of adjustment it would be for you. Walking outside, I didn't have garbage cans. Where I grew up in the projects, across the street there was a dump where dump trucks would dump garbage. There were a million seagulls. You can imagine the smell, imagine the size of the rats that that would come out of there. Southern had really green grass, Crab Orchard places like that. You didn't have to lock the doors. But, you know, I couldn't stand on the corner and catch a bus. I couldn't.

There were many people who welcomed me to SIU and who I grew to love. Steve Hemmer and his family were influential in my success and life. They treated me like a part of their family, and I will always love them. I also want to acknowledge my dear friends Leonard Hopkins and Lawrence Love, and my roommates and everyday supporters, Tim Cruz, Joe Laws and Joe Hage.

From a playing standpoint, I had blown out my hamstring in my last game at Westchester, so when I came to Southern, I should have just stayed back and let it heal, because those were very trying years. Even though I started, we were running the wishbone — the wrong offense for the wrong personnel. In '74, the other teams were laughing across the line of scrimmage, because we were much more talented than they are. It was frustrating. We had a big dropback quarterback in Leonard Hopkins with a fabulous arm. So thank God Rey Dempsey came.

SD: Tell me about Coach Dempsey.

AH: First of all, the impact that man has, a God-fearing man. He refers to himself as my father and he's a blessing. He knew he had to change the culture there, but he had to get into the minds of people. And once you change the minds of some of the best people on the team, everybody else will fall in place. So Coach Dempsey was tough in the beginning, but he wanted to make this environment better. He wanted to change the culture. He wanted to change the program. He wanted to build it. You know, it happened overnight. We were one of the top five schools in the country for best reversal of wins and losses from the previous year. Once everybody started buying into that, we were a dominant force.

SD: Obviously, he figured out how to use you, because you had an unbelievable year in 1976 — almost 1,600 yards rushing, eight, 100-yard games, All-American.

AH: He instilled confidence in me, and in that spring, we started a weightlifting program. We never really had a weightlifting program, so when I came back in the fall, I could bench press 300 pounds 12, 15 times. There's no other formula for success except hard work.

I loved when we would play a team and in the interview prior to that, he would tell them we're going to run the ball, we're going to run it, because it was a challenge. I love to be challenged. I’d be lined up in the I-formation, and the other team would say, "It's coming here, it's coming here, it's coming here." While they were barking out the signals, I would say, “it's coming right there and on two!” And then the referee would say, be quiet. I knew they weren't gonna stop it. That's the mentality that I had. I unequivocally felt I was as good as any back in the country.

SD: Well, you were. You finished second behind Tony Dorsett in rushing.

AH: That's correct. I remember you had all these big schools have runners up there. You had Pitt, USC, Oklahoma State, Michigan. Week after week, I was putting in the yardage and I believe I was AP Player of the Week two or three times.

SD: What do you remember about the game versus Northern Illinois when you set an NCAA record with 217 yards in a quarter, 319 yards in the game, six touchdowns.

AH: So we had a tremendous downpour, so much so that the day before, they could not have the Homecoming festivities. I mean, it was raining hard. On Saturday morning, we could not warm up like we would have liked to normally. We were underneath the stadium then.

As I was getting taped up, and I believe this was a ploy, they hand me a note that said the Northern Illinois coach said, “he's not going to do much today. He's not going to do much today.” And he was challenging me. That brought out the New York, that Bronx mentality. And I said, “put an extra strip of tape on there.” And they did. So I was determined to let him know, don't ever disregard what I do in my mind quietly.

I remember it was incredibly slippery in the beginning, but we had the turf, so that was great. I had some long runs, and when it gets wet, the equipment, your pants and everything, it gets heavy. I can remember making some long runs, and if you look, I'm breathing hard, and everybody else is jumping up for joy. And the defense was so incredible that we kept getting the ball right back. The major news sports stations, ABC, NBC, CBS were asking, did he break it yet? Did he break it? I had no idea what they were talking about, but I could hear them say that. I was just trying to catch my breath to get back out there. My understanding is that they panned away from the games that they were showing and took a picture of Southern Illinois.

There are people that to this day come up and tell me if I meet with them that they sat through the game and I thanked them graciously because it was not good weather. Some of the smarter people watched it in the Student Center, but I thank God for the opportunity.

I only played into the third quarter, and after the game, Northern’s coach comes running up to me and said he was sorry. He didn't mean what he said, and I'm like, well, the damage is done already!

SD: You get drafted by the Chiefs and spent the next three years battling to make an NFL roster. What was that experience like?

AH: It's a business in the pros, and I didn't have enough experience. First of all, I was still learning how to play running back. I would fend off a lot of recognition because of what was drilled in my head by my father. I had (AD) Gale Sayers, who spoke very highly of me and said I can't miss in the league, and I appreciated that.

SD: Saluki Football was highly celebrated for winning the I-AA title in 1983, and rightly so, but it appears your era laid the groundwork. Would you agree?

AH: Just the fact that we had the opportunity with Coach Dempsey to understand the next step, what it would take to be great. What a blessing it is to leave that particular time period with a legacy of winning. Prior to 1976, we walked around the school, we didn't get the attention and respect. It was a complete turnaround.

I respect the 1983 team that won the championship. I know several of the players there like Terry Taylor, and I respect them all very, very much. I'm glad that they did well, and all the other coaches that followed from Coach Kill to Coach Hill in this program, to continue to set the standards and do well. But understand that the year before I got there, they played Oklahoma State. We would play people like West Texas State, Tulsa, East Carolina. East Carolina was dominant, and Marshall. Teams like Eastern Illinois, Western Illinois were Division II back then. We didn't even see SEMO.

I'm not putting any of that down, but there is a difference, and we hope that it gets recognized. I applaud all the people that played, because when you're good, you're good at any level. And that's with an exclamation point.

SD: Tell me about life after football.

AH: When I ended my football career, I was discouraged and it took the life out of me to play football. I didn't have an agent. The teams would be calling my mother and I had to call my mother at home and she went down the list. So, of course, I made some mistakes, but I don't regret anything. I don't think anybody doubted my talent.

Then after football, I always loved sales. I went right into sales into import-export business containerizations, and moved up to regional and national manager. I started with a printing and advertising company in Baltimore, Maryland, and got promoted to Michigan, where I am now. I found that not only was I good at selling things, but in terms of managing people. I used a lot of psychology, and if there’s one thing I felt that could go back and do over, I would go back and major in psychology.

I started my own business in between the company I left originally and the company I'm with now, which is I'm a national sales director. The name of the company is IndoorMedia. They do the advertising in the supermarkets, and I have several states. So I really enjoy the fine company. I enjoy working with people, hiring and training new people and managers.

And you know, Tom, I think that's the part of my life now that I'm going to focus on is leaving what my legacy is going to be. I get time to speak to groups of people periodically. I just understand that when you can encourage people and show them the way to success, there's nothing better in mind.

And of course, when you understand the Lord and our Savior, that is the ultimate.

Comments